I tackle a couple of iconic astrophoto targets, the Horsehead Nebula and the Great Orion Nebula

AstroBlog

I tackle a couple of iconic astrophoto targets, the Horsehead Nebula and the Great Orion Nebula

I recently added the ZWO “EAF” motorized focuser accessory to my photography setups. Since focusing is one of those “critical path” activities that affects the quality of your photos more than any other one single factor I thought it would be a worthwhile investment of $249. Some of these units are well up over $450 and beyond so if this helps, I’m considering it a bargain!

Bill

I seem to get a big charge out of getting photos with multiple deep-sky objects in them, so what better target than the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies? It’s an area of the sky just East of Leo (in Virgo actually!) that is the location of the nearest ‘super cluster’ of galaxies. If you hold up your hand at arm’s length, fingers spread in this direction of the sky you will have over 2000 galaxies behind your hand.

I took this image in the early part of the year and have been working on it in Photoshop for a few months now manually cleaning the camera noise out of the image so you can see the faintest, most distant galaxies against a nice black sky background. Well I finally finished and here it is:

Markarian’s Chain in the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies. I have Identified over 200 galaxies here. Click for a bigger version.

Heart of the Virgo Cluster

I had shot this area of the sky before but with a telescope that sees a lot less sky but I wanted to see how many cluster members I could get and it would also serve as some kind of a benchmark as to “how deep can you go”.

The image to the right was promising: it had pretty good detail in the edge-on spiral galaxies that flank the two big elliptical galaxies M84 and M86 and just peeking through the noise there were some background galaxies–I think I counted 17 or so at one point.

Distant galaxies look like little fuzzballs on an image and even though they are really big they are also very far away so they appear as little smudges, barely discernible as “non-stellar” blobs lurking above the noise-floor of the image.

The hardest thing about processing these images is finding the right settings and procedures to get the part of the image you want to be easily visible and the camera noise down so it isn’t visually distracting.

Well that turned out to be impossible with this image–the faint stuff was so diim that if you wanted to see it at all you had to stretch and amplify the light curve so much that the noise came right up with it as a speckling of tiny variously colored squares. I tried a number of automated techniques to get rid of these things and everything I tried was also damaging the parts of the image I wanted to keep.

So I took a deep breath and resigned myself to the fact that I would need to clean this image manually by selecting an area of the screen, then deselect the parts of the image I wanted to keep, then replace everything else with a nice sky background color. I did this about 300 times over four months to get through the entire image.

Closeup of M88 from the upper right of my image. The only galaxy with any real detail here, it’s one of the closest at 36 million l.y.

So what do you do with an image like this? On one hand it’s amazing that I, as a hobbyist can take pictures of something that is 50 million light-years away! On the other hand, it’s just a bunch of fuzzy blobs in a nice star field. The only galaxy in here that shows any structure at all is M88 at the top right and there really isn’t any visual ‘wow factor’ on par with a great shot of some pinkish cloudy nebula with it’s exquisite detail.

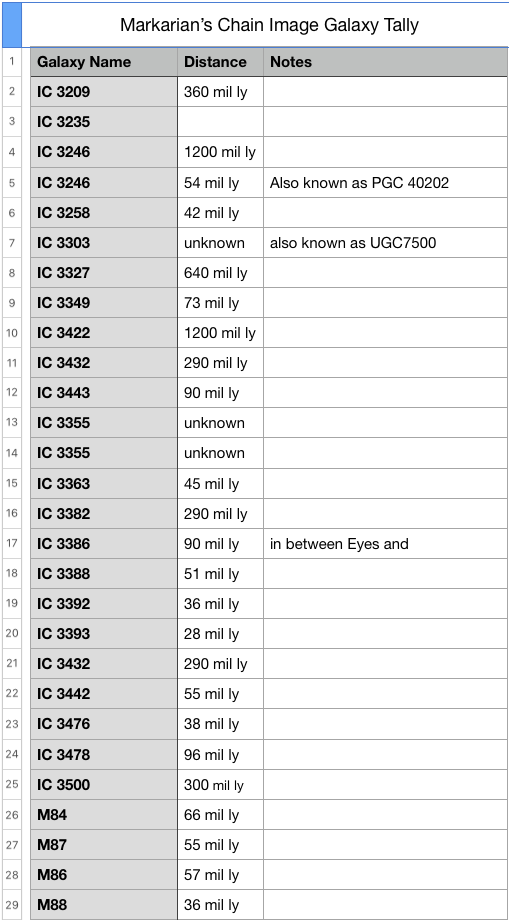

I really wanted to know “ok, what exactly do you have here” in this image so I decided that I would compare my image to a map of that part of the sky from my astronomy program, “Sky Safari Pro”. So I got the approximate area of the sky up on the map on one screen and zoomed way in on my image to start seeing what I could find on my map and was it visible in my image. Every time I found one I put it into a spreadsheet I started with the galaxy name, distance (if known) and a note if there anything notable.

I had been telling people at my stargazes that I thought there were maybe 35 or so galaxies in the image, based on me just poking around there. Well as I started cataloging I realized I was waaaaay wrong about that; it’s more like 200!

Map of the Virgo Cluster from Sky Safari. This is the approximate area of my photo

Once I got into it and had finished all the bright easy ones (about 20 or so) I dove in deep and started trying to identify the smallest little smudges on my image and seeing if they showed up on the map. Or sometimes I would look at the map and see if there was a wisp of light where there was supposed to be something. It was like the Russian dolls of galaxy hunting, the harder I looked, the more I would find. Here’s the area around M86, the largest of the two elliptical galaxies at the center of the image, both map and photo, side by side.

M86: Map and close-up of my image. How many galaxies from the map can you find one the image?

So the big galaxy, M86 is 57 million light years away, putting it squarely in the center of the Virgo Cluster whose members range from the relatively near 30 million l.y. to roughly 70 million l.y. on the far edge of the cluster. Well I was astonished to find out that galaxy PGC 169281, visible in the halo of M86 was 1 billion, 700 million light years distant! just barely above the noise floor of my image. Well this was now getting really exciting and for a week I sat there comparing map to image and cataloguing what I could find on the spreadsheet.

Since my noise cleaning activities took place over such a long period of time and my methods got more refined I realized a probably ‘cleaned’ a number of galaxies out of the image in the upper right (where I started the process) before I had become aware of just how faint some of this stuff is. I gradually became aware of what a slightly blurry star looked like compared to a distant galaxy. This process was also hampered by the fact that the image and the map were in slightly different orientations. This was no big deal when you had super easy to identify landmarks in the image but when I got out to the edges it got really difficult to make absolutely sure I could reconcile the image against the map. Sometimes I’d sit there for half and hour trying to get my bearings before I could be sure of what I was seeing.

So who was the distance winner in the image? Well that would be PGC 40480 which is 6 billion, 400 million light years away and is receding from us at 37.8% of the speed of light due to the expansion of the universe! Well this blew me away to find that one. That would mean that the light from that galaxy had been traveling in space for about half the age of the Universe. Or put another way, the image that I got (as diffuse and smudgy as it is) is of the galaxy as it looked 6.4 billion years ago, before the Solar System and Earth existed by 2 billion years, when the Universe was about half it’s current age!

So the real fun in this image is not the image itself it turns out, but what it represents and some good geek factor that just an average guy with above average motivation could even detect something like that.

Bill the Sky Guy

July 27th, 2019

Here’s the list of everything I could find and positively identify. I finally just had to stop and I estimate there are probably 25 more little smudgies that I didn’t get to or couldn’t reconcile against the map.

In just visually surveying the distances listed here, it really seems like there are three distinct galaxy clusters in depth in my image.

First the Virgo Cluster itself, 30-70 million light years, then there’s a second group from 300 to 800 million l.y. Out at 1 billion to 2.7 billion l.y. there is a 3rd cluster. I don’t seem to be easily able to track down the names of these clusters or perhaps they’re all considered part of some larger supercluster–this is probably above my amateur astronomer pay grade. Suffice it to say that it really brought nome to me the three-dimensionality of the Universe and kind of gave me a window to the thrill the earliest researchers must have had when they started getting these images for the first time, which wasn’t all that long ago, and during my lifetime!

A post detailing some new gear and methods I’ve been trying.

August is a really good time to get out of South Carolina and get an early taste of Autumn so I took a trip up to the mountains near Asheville North Carolina for a week of astrophotography and observing.

I had upgraded several key components of my setup since last year–the 16-inch Dobsonian had been replaced with an 18-inch Obsession Dobsonian, The 8-inch Astrograph scope had been replaced with a 10-inch version that is much easier to adjust the mirrors on, and the camera itself had been upgraded to a much larger sensor to image some of the large nebulas that are out there and actually cover a fairly large amount of sky.

I had also significantly upgraded my knowledge and procedures and probably the best $250 I spent this year was for a polar alignment camera called the “PoleMaster” by QHY. After all, everything I listed before is useless if your image is blurring all over the frame because you can’t track the sky correctly–damn spinning Earth!

Monday was the first night and it promised to be a good one so I figured I would set up both a photography scope and the big Obsession which I could look at my “faint fuzzies” while the photo scope was taking exposures that would total a few hours worth.

I got there a full two hours before sundown because I knew this would be a long, complicated setup and wanted to make sure I was covered when it came to power; I was using batteries only since understandably there’s no 110v at the Mt. Pisgah Trailhead parking lot!

First thing I discovered was the strap that holds the 18-mirror in place on the big scope had worked its way loose on the trip up and the mirror was just sliding around on the mirror cell! Glad I discovered that before significantly tipping the assembly upright. A quick trip to the toolkit (glad I remembered it!) for a socket wrench and a pair of pliers and I had the mirror nicely snugged back into position.

There were two photos on my “gotta have it this trip” list: the North American Nebula in Cygnus, and my personal favorite object, the Veil Nebula, a supernova remnant, also in Cygnus. I had two photographic scopes with me, a small wide field refractor and the 10-inch astrograph. Both the North American and Veil are big objects in the sky so the refractor was the instrument of choice for both and I was pleased to take the first serious photos with the new Triad nebular filter for astrophotography which was an $800 filter for the camera. It was supposed to be the bees knees and as it turns out, it is!

I got things aligned, checked out and running smoothly and had the computer take 240 15-second exposures of each object, for a total exposure time of 1 hour each. I wish I could have taken some longer exposures but after 2 years of fiddling I still don’t have automatic guiding working properly so this was the best way to assure that I wouldn’t come away empty handed.

While this was going on I was at the big scope observing all the great stuff in the summer Milky Way and all the things you can’t really see well without an inky black background sky. Four planets in the sky as well made for some fun observing where normally I’d be sitting in the chair in front of the photo computer playing Angry Birds!

About 4am I was toast and became incinerated toast as it took me almost 2 hours to pack everything back up and squeeze it into the car arriving back at my place in full daylight!

Here are the two images I got that night:

The North American Nebula (NGC7000) in Cygnus, just off the bright star Deneb.

The Veil Nebula (eastern portion); also known as the Network Nebula

Night Two, I Dew

My second night out this trip looked to be promising weather wise and I decided to just go with the photographic setup this time since after all it was my vacation and yesterday was freaking exhausting!

The plan tonight was to use the 10-inch scope and get a shot of the Dumbbell Nebula (M27) since it’s a large planetary nebula that would really fill a decent part of the frame and the new Triad filter would help a lot with contrast. So I got everything set up, polar aligned the mount with PoleMaster, centered my target, took a couple test exposures to verify that I wasn’t over-exposing the brighter things in the image. Then I told the computer to take another sequence of 240 15-second exposures while I settled in for the long haul in Angry Birds2!

You don’t actually see a finished looking image come up on the screen when you’re taking them; it’s only after stacking the hundreds of exposures on top of each other in the computer (after throwing away the bad ones of course) and playing around with it for a couple hours in photoshop do you actually see anything like the images above. So at the end of the run I pull up the last image and make an attempt to do some editing to make sure I’ve got what I think I got and something’s weird with the center of the image so I keep playing and eventually come to the conclusion that the image is unusable. So I look back 50 earlier in the shooting sequence, same thing! I eventually find out that all 240 images are toast and I’m suspecting that for the first time ever I’ve got dew on the camera lens.

The way it works with these sensitive cameras is that in order to keep noise from stray electrons down they provide a thermo-electric cooling circuit that will cool the camera to 30°C below ambient temperature. Even though it was 70°F in the air the camera itself was below freezing and so I unscrew it from the back of the scope and see a nice little pile of dew drops from the warm moist air have condensed on the glass plate that protects the actual light sensor chip. Damn! Hour and a half wasted.

Now I have to clean it somehow without leaving streaks! So I get a few Q-Tips that I would normally use to clean eyepieces with and gradually absorb all the moisture to the point where I don’t see any residue. I think I’ve got it clean enough but there’s only so much you can see under a red flashlight so I decide that it’s the best I can do right then and head on to the next object.

In an attempt at “instant” gratification I decide to shoot a star cluster in the west since M27 was now in an area of the sky that was getting some low cloud action. Star clusters are a lot easier to process after the fact than nebulas I’ve discovered and I was determined not to come away from the entire evening empty handed. So I chose M11, the Wild Duck Cluster 6100 light-years away in constellation of Scutum, which is in the general direction of the center of our galaxy. It’s a cluster of about 2900 stars in a rich star field of the Milky Way.

I shot sixty 20-second exposures eventually being able to use 32 of them in the final image:

Messier 11, the Wild Duck Cluster, click to open a larger version of this image.

They call this the “Wild Duck” because the stars on the bottom sort of form the familiar V shape of ducks or geese flying in formation, It’s a stretch, I know but hey, I didn’t name it!!!

By this time it was closing in on 3am and there were a lot more clouds in the sky, enough that no matter where I decided to shoot I was going get overrun so I decided to call it a night.

Wednesday the weather was bad enough that it wasn’t work making the trip out and setting up so I had a night Movie Night In at the AirBnb I was at.

I went out Thursday and set up the big scope for a night of pure observing bliss! I got clouded out after couple hours but not after some really spectacular high magnification views of Jupiter. Saturn and Mars, which was only a couple weeks past closest approach. It’ll be 2033 before we see it this good again!

The weather Friday was the worst all week so I decided to go home a day early so I could play golf all day Saturday instead of driving.

Bill the Sky Guy

August 2018

I was able to get out for a couple imaging sessions earlier this month during the moonless night period following Full Moon heading up to first quarter.

While I still have a lot of work to do to arrive at a truly solid equipment setup and procedures that are bulletproof, I have managed to shoot a couple things before I lost them in the western glare for the year. The amazing number of galaxies in Leo and Virgo have been a theoretical target of mine and in keeping with a theme I seem to be developing of multiple deep-sky objects in the same shot, I decided to capture the combination of galaxy M108 and M97 the "Owl Nebula" just outside the bowl of the Big Dipper.

2017 was a great year for me and Astronomy, Astrophotography, and my Sky Guy shows. Attendance at the Stargazes every Monday Tuesday and Wednesday is really picking up with the (finally!) warmer weather and I'm hearing "saw you last year and it was terrific!" a lot. Every now and then I'll get a story of one of the kids who 'has their own scope now' and who knows where that could lead to! It's great to know that I might have cracked open a door for them that might lead to a life in science; or financial ruin from buying larger and larger telescopes. I can stop any time, really…

M81 (bottom right), M82 (upper right), and the surprise NGC 3077 (lower left) which I didn't even know was there!

I've finally found a couple of nights where I could get out with the complete new rig: the Losmandy G11 mount, the new wide field camera and the small refractor telescope that sees a good chunk of sky.

The problem with the old rig was that the mount refused to be auto guided (although this photo isn't either but that's a whole 'nuther subject) and the camera's detector size was so small that you couldn't even fit the entire Moon in the frame and I wanted to take bigger shots than that so after a liberal application of JP Morgan's Magic Ointment ($$$) I have a new camera with a sensor that's five times bigger! This was the first night I had it all out and working at the same time.

My first experimental shot was of the Orion Nebula, which is quite large if you're going to get it all. As it turned out I was very happy to discover that not only could I get the entire nebula in the frame but also some of the neighboring stars from the Orion's Sword area so that in and of itself was pretty exciting.

While I was there I moved over to the Horsehead Nebula (just south of the easternmost belt star in Orion) just to see how that would come out but after four 90-second exposures I saw the stars were smearing pretty badly but was heartened to know that I'll be able to get a shot of not only the Horsehead but the Flame Nebula as well when I take that shot for real.

So I slewed on over to one of my favorite galaxy pairs, M81 & M82, near the bowl of the Big Dipper. This is a great pair visually in the 16-inch scope and at 12 million light years distant is challenging but still accessible for the gear that I have. I've always loved the contrast of M81 as a wide open, beautiful classic spiral galaxy and the gritty edge-on M82, which is nicknamed "The Cigar Galaxy" from the way it appears in the eyepiece. M82 is a really active galaxy in terms of star formation and there have been two supernovas there in the time that I've been into astronomy.

So I shot twenty 90-second exposures of this pair and things seemed to go well but you never really know until you get home and start combining them in the computer and seeing what you've really got!

After many attempts at processing I finally hit on a combination that I liked so the final image is the fifteen best exposures stacked and light-level stretched to get this final image. It's still a touch smeary if you really zoom in a lot which tells me I need to get better polar alignment for the mount which continues to vex and elude me. But at least I know now that it's me, not my gear that is the limiting factor!

Next target will be the Crab Nebula in Taurus I think!

Carpe Noctem!

Bill

Well, the 2017 Solar eclipse has come and gone and all in all it was an amazing experience! This was my first total solar eclipse after seeing a few partial ones through the years from Cincinnati. The most recent one I saw there was a 93% eclipse which you would think would makes daylight quite dark but I learned that day that the difference between a total eclipse and a partial is like, well, night and day!

I had been hearing about this eclipse for over a year, and spent a good solid couple months preparing for it. Since this might be one of the few total eclipses I'll see in my lifetime (although I am looking forward to 2024) I wanted to make sure that I got some good photos. The hard part about that is that these things are notoriously difficult to photograph and you only really have one shot at it. Since this was my first I didn't want the task of photographing it to detract from just experiencing it without getting bogged down in the details of equipment and all of that, so I wanted to make the photography as automated as possible.

I eventually decided to use four cameras to capture the event; two still cameras and two video cameras. The main camera was my astronomical CCD camera which looks through the telescope and then it Is controlled by a computer which actually takes the pictures and stores them on the hard drive. In advance of the event I had to do a number of test sessions with this set up to determine the proper exposure and how to get the telescope mount to track the Sun when you can't see any stars in the sky to a align to the north star. As it turned out the image from this camera combined with the telescope I was using did not allow the entire sun to fit into the frame which was unfortunate but the solution to fix it was really expensive so I decided to make the best of it.

The second camera was a mirrorless DSLR which was also attached to the telescope mount so it would track the sun across the sky. The main job of this camera was intended to take wide-angle shots of the Sun during the totally eclipsed phase of the event. My initial testing determined that the lens came with this camera did not zoom far enough in to get a good high resolution shot of the Sun and the corona so about a week before the event I ordered a new, longer lens that gave an acceptably large image although hindsight being what it is I wish it could've zoomed in a little more.

The third camera was one of those little GoPro video cameras which I decided to stick high up in the air with its wide-angle lens seeing both of us on the ground and looking northwest where the Moon's shadow was going to be coming from. In doing reading about the past eclipses I have heard that in the seconds prior to being engulfed in totality you can actually see the moon's shadow rushing at you if you have the right vantage point. The perfect scenario for this would be being on the top of a mountain with a valley below you in the direction of the approaching shadow. It is said you can see a diffuse dark shaft rushing at you at a speed of 1500 mph!

My chosen location didn't include a mountain but I thought I might be able to see something if I pointed a camera that direction which turned out to be a good decision.

The fourth camera was almost an afterthought but after re-reading an excellent article on photographing solar eclipses in Sky & Telescope magazine I decided to take one of my video cameras, fashion a temporary solar filter for it, and roll video not so much for the pictures but for the sound! I didn't know how many people were going to be around at that time but it is said that the sound of a bunch of people watching a total eclipse is electrifying and since this was easy I thought "Why not?"

One of the first things I had to decide was where to see it from. It was only going to be a 98% eclipse where I live so I knew I would have to travel at least a little bit to get on the centerline of the moon’s shadow path across the United States. I know from living in Hilton Head that the weather along the coast is highly variable and difficult to predict so I thought a more inland location would be better.

There were a number of highly accurate, high resolution maps of the path of the Moon's shadow posted on the internet so I studied these and selected a spot right on the centerline just south of Columbia South Carolina in an outlying town called Gaston. The eclipse maps could only get you in so close so I called up Google maps on my web browser, noted some landmarks that were directly on the centerline on the eclipse map and then zoomed in farther on Google maps and using the street view function was able to cruise around the neighborhood looking for a suitable place with no obscuring trees closeby, easy access etc.

My primary place was a small one-story church called Shiloh United Methodist Church which when I tried to contact them I discovered that their phone had been disconnected so I assumed they wouldn't be having any big eclipse carnival that day. One bullet dodged…

It was a good two and a half hour drive to Columbia and I was planning on taking the back roads up since I couldn't absolutely count on I-26 being clear all the way since the shadow path followed it fairly closely and could be choked with traffic. I had a lot of gear to set up so getting delayed in traffic was simply not an option. I took one small wrong turn on the way and for the first time in my life I actually had to avoid a rooster on the road! Guess he had to get to the other side…

I arrived about 11:15am which left me plenty of time before the beginning of the eclipse at 1:15pm. The first thing I set up was the GoPro camera because I wanted to make a time-lapse video of the setup process. Next was the telescope mount and scope, do a quick polar alignment by using an iPhone and a sky map app, and then attaching the still and video cameras.

The astronomical CCD camera was hooked up to the telescope and although I know it was total overkill, I programmed it to take a picture every second for the entire 3 hours of the event. I was thinking that I could sequence them together and make a movie of the roughly 4000 still images that would show the Sun getting gradually covered up by the Moon, become totally eclipsed, and then have the Moon recede getting everything back to normal. Fortunately there were a couple of nice sunspot groups on the Sun that day.

The Moon just starting to cover up the Sun

The Moon would take about 1 hr 15 minutes to completely cover the Sun and once I was assured that everything was running smoothly I did what any sane person would do, I had lunch! This was thoughtfully provided by my neighbors back in Bluffton who decided to come along a bit later for the show. During this time we had at least two people stop by wondering if we had any eclipse glasses for sale. Talk about last minute shopping! My neighbors Sam and his wife Shannon and Kelly from the front desk at Grande Ocean (where I do Sky Guy on Tuesdays) and her boyfriend were fun to hang out with and I explained a few things about what we could potentially see as we got within a couple minutes of totality.

The Eclipse Crew

A versatile accessories case is a must!

I was surprised that given this ideal location that there weren't more people showing up but I guess if you're lucky enough to have a total solar eclipse show up over your house some day you don't really need to drive to the other side of town to make it last 2.5 seconds longer.

My rig for the day. Notice that even the cameras that weren't running had solar filters on them.

I had my computer set up in the back of the car taking that picture every second of the eclipse's progress but the image on the screen made for a handy way to monitor the progress of things without having to crane your neck although I thought the view through the eclipse glasses was very cool.

As we got within five minutes or so I started the video camera and took some test shots with the still camera which I discovered during my previous testing could be controlled from an app on my phone! This was great because I wouldn't have to worry about my finger pressing the shutter button and causing the whole mount to shake a little causing blurring or misalignment of images.

The still camera was the one I was really hoping to get the best photos of the total eclipse from. I had it set on a bracketed exposure setting which means that it takes 3 shots at progressively darker exposure settings, one at the center, and 3 gradually brighter images for a total of seven pictures at seven different f-stops–one of them had to be right! During the total phase of the eclipse I pressed the shutter button on the app as fast as it would allow and took over 400 images in two and a half minutes. I also planned to be able to use a number of images from each seven image sequence in a layered photo using the best parts of each in what is known as HDR (High Dynamic Range) photography. This all worked amazingly well as the image below shows.

This image was taken about halfway through totality

I re-centered the image from the CCD camera on the telescope since it had a tendency to drift and needed a touch up every 5 minutes or so and double checked the GoPro to make sure it was still running in video mode; it had inexplicably stopped recording on it's own earlier in the day so I wasn't going to blindly trust it. Confident that my tech situation was as good as it was gonna be we started getting set for the main event.

I was pretty sure I wasn't going to be able to visually see the moon's shadow rushing at us because of the church and a tree in the way so I trusted that if it could be seen the GoPro would get it.

The light was really starting to look strange now. We were down to about 30 seconds before the onset of totality and there was just the tiniest of sliver of sun showing now.

You would think that with 99.x% of the Sun covered up it would be damn near dark and while it was obvious that the sun's light was drastically diminished it still had that quality of "weak daylight" or how strong the sunlight might be on a more distant planet like Mars.

This was the time to look for what are called "shadow bands" which is a scintillation of the Sun's light very much like the way stars twinkle, except this was projected on the ground; the thin beam of light is easily buffeted by the Earth's atmosphere causing this shimmering effect seen on the ground all around you. I didn't find them all that obvious but the other people in the group said they saw them; I might have been distracted with everything that was going on in my head!

The last gasp of the Sun's light to go before totality leaves just one little spot of the photosphere showing creating what's known as the "diamond ring". The still camera got a number of good shots of this. This only lasts about 15 seconds getting weaker and weaker until just like that, you are enveloped in darkness. It's not the same kind of dark that you get at night because there is still quite a bit of diffuse light coming from the corona (the Sun's outer atmosphere) but it's definitely not light. The street lights came on, birds starting chirping (they were probably thinking, "Wait, seems like I just got up!") and there was an audible gasp from everybody watching.

Totality was supposed to last two minutes and thirty five seconds at my location and from the onset of the diamond ring I started firing the shutter of the still camera, each push of the remote shutter button on the app taking seven images. Later I found out I took over 450 images in that 2.5 minutes. Once the diamond ring was done the eclipse glasses came off and you could experience this in it's true naked eye glory.

There's a lot to notice during an eclipse and a finite amount of time so I had my checklist running in my head. There were four planets in the sky, Jupiter off to the West which was far enough away that it was still a viable evening object just after sunset, and Venus, even farther away to the East making it a brilliant object (bright as a low plane) in the sky just before dawn. These were super easy to spot and now I can say I've seen Venus and Jupiter during daytime!

In theory you had both Mercury and Mars on either side of the Sun but they were supposed to be much dimmer and pretty close to the Sun and I didn't easily detect them and decided not to really waste any precious "totality time" on them. The bright star Regulus (in Leo) was right next to the Sun and while I couldn't see it visually it does show up on some of the photos.

Words are inadequate so I won't even try, but suffice it to say that a total solar eclipse is a truly unique natural spectacle on the grandest of scales. Here are a number of photos from the totality:

I processed these shots in a variety of ways to try and feature the detail in the corona streaming away from the Sun or to accentuate the prominences and fiery outcroppings from the Sun's surface.

It was really pity that I couldn't get the entire Sun in the camera that was hooked up to the telescope. I hadn't planned on using those shots during totality since I knew my exposure was set for a big sun disk with a solar filter on the front of the scope but after about 30 seconds of totality I thought "you've got nothing to lose" so I whipped the solar filter off the scope and ended up getting about thirty cool alternate shots. Thankfully I remembered to get the filter back on there quickly as the diamond ring appeared on the other side of the Sun this time, signaling the end of totality and no more looking at the sun naked eye for the rest of the day.

I've put together a video that combines the various videos and still images into something that is hopefully entertaining. Click this link to view it.

Well to say that the rest of the eclipse was anticlimactic would be an understatement, but totality is a hard act to follow and we were just seeing what we had seen the previous hour and fifteen minutes, just in reverse now. I kept monitoring the telescope camera, finished my sandwich, stopped the GoPro and occasionally fired off a salvo of pics on the still cam to capture the Moon's retreat.

This was the first day of my vacation for 2017 so after it was all over I drove to Atlanta to visit some friends and then headed up to Asheville NC for a couple of nights to see what my new 16" scope could do from a truly dark site at some altitude, and to see if I could get some deep sky astrophotography in.

The site at the Mt. Pisgah trailhead was recommended to me by the head of the Asheville Astronomical Society and didn't disappoint. There was a friendly local couple there who said they were regular "Sunset watchers" and I gave them a bit of a sky tour while putting the 16" through it's paces which didn't disappoint.

On the 2nd night which I was devoting to imaging, I went through the involved process of getting the scope truly polar aligned. I started with targets in the West since they were on their way down and thought the eagle nebula (M16) would be a good target. The mount was cooperating and went right to it and was easy enough to get centered for a nice shot. I used my brand new focusing mask to get exact focus and then stood around while the computer took twenty 2-minute exposures which I later stacked together in the computer and processed into the image below.

M16, the Eagle Nebula; 40 minutes exposure time.

I was pretty confident that I was getting good shots and because of the time and effort involved in getting everything set up and working I decided to try M8, the Lagoon Nebula which is popular with my stargaze audience because it's an open star cluster, a reflection nebula and a dark nebula all in the same field of view.

For the shot below I took twenty 90-second exposures but had to throw out about five of them because the mount was not being auto-guided and some of the individual exposures looked more like teardrops than stars. Nevertheless I'm very happy with this image:

M8, the Lagoon Nebula complex

As I've mentioned elsewhere on this site I've been trying to take deep sky astrophotos one way or the other with only marginal success since I was six years old and now that I'm almost 60, it's really gratifying to see that if I give myself some time, I can figure things out! Eventually…

Bill the Sky Guy

What are the kinds of things you can see during a total solar eclipse? Well here's a few things you can watch for in your two minutes and thirty seconds under the Moon's shadow!

I'm very excited about the coming summer observing season as there are a great many sights to look forward to and I'll relish being able to show them to people at the three weekly stargazes I do for the Marriott Vacation Club organization.

Why so excited? Lots of reasons actually. First and foremost is the new 16" telescope I put in service back in January. This will be the first season of looking at the summer Milky Way and all of the great things you can see as you look towards the center of our galaxy. I haven't been though one complete year's worth of observing with it yet so it will be a real treat to see what it can do to enhance all of the favorites I've been looking at with the 8" scope I've been using for the past thirty years. I've been amazed to discover that I can actually see the edges of the spiral arms in the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) or dust lanes in galaxies that are 12 million light-years away like M82 and the Sombrero Galaxy. The 10" scopes that two of the three Marriotts have did a real good job with some of the cloudy nebulae near the center of the Milky Way last year, I can't wait to see what the 16" with a Lumicon Ultra High Contrast filter is going to see.

Then, there is the even more exciting prospect of what totally new things will I be able to see that simply weren't within reach of the old equipment. Comet Johnson has been a surprise fun thing to see lately but I'm wondering what kind of look I'll get at the North American Nebula or the Eagle Nebula where the Hubble took that famous "Pillars of Creation" photo.

The asterism we call 'The Summer Triangle' is already starting to be in the sky as we wrap up the stargazes around 10:30 or 11PM, so in another month we'll have it in the sky all night. This is one of the most fertile places in the sky for finding great things to look at in a contained area. You can find truly stellar (ar ar) examples every kind of deep-sky object (except perhaps galaxies) in there: open and globular star clusters of various sizes, expansive nebulae, double and quadruple star systems, planetary nebulae (dying stars), supernova remnants (truly dead stars), and the most fertile hunting ground for exoplanets (planets around stars other than our Sun, which sadly are still beyond the reach of even this scope).

Omega Centauri (NGC 5139)

Recently, one of the daily astronomy newsletters I subscribe to mentioned something that caught my interest: the globular star cluster Omega Centauri which is by far the finest globular cluster in the sky! Well that's what they say except I've never seen it. Most of my astronomy 'career' was done in Cincinnati which is at 39 degrees north latitude. But down here in Hilton Head SC, I'm now at 32 degrees which allows me to se farther down into the southern sky and after checking in with my astronomy software it turns out that Omega Centauri cluster will be at it's highest point in the sky about 10:30PM this week and we have the ocean as our southern horizon so there's a pretty decent chance to see it!

So what's so special about Omega Centauri? Well it is far and away the biggest, brightest globular cluster in the sky, more than twice as many stars as the number two globular and it's as large in the sky as the full moon! After reading the article I learned that this just isn't an ordinary "bigger than usual" cluster, it is probably the remaining nucleus of a dwarf galaxy that orbited the Milky Way (one of the 48 dwarf galaxies known to do so) and got so close the the Milky Way's gravity stripped away and absorbed all of the outlying galaxy members leaving only the tight nucleus intact.

Why do they think this? Because Omega Centauri has a large-ish black hole in the center of it which is a feature that is common to galaxies but not at all with your 'garden variety' globular cluster. Also the population of the cluster is a bit more varied that globulars which tend to be very much all old stars of similar size and brightness. I'm going to see if I can get a pic of this somehow in the next couple weeks.

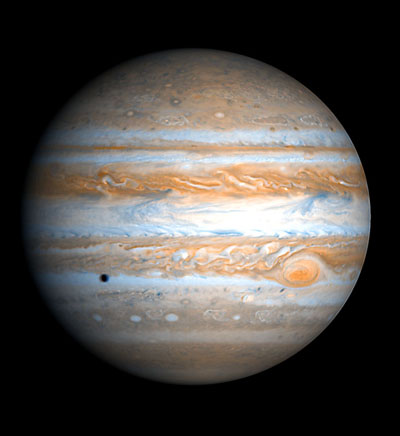

Jupiter, largest of all the planets

Jupiter is now high in the sky for good viewing at stargaze time and it will be a great sight all summer. I never really could make out the great Red Spot in my 8" but in the 16" it's really quite obvious if you know what you're looking for.

Jupiter's four main moons put on quite a display every night with eclipses, occultations and shadow crossings to keep track of, all very easily displayed by my new astronomy software, Sky Safari 5 Pro which is incredible. It even points the telescope for me if I want!

It really is impressive to see the amount of detail you can find in the could bands at 250x and above

Saturn isn't quite ready for early evening viewing just yet but in about another month it's should be available. It'll be interesting to see how many of the moons I can see with the big scope-I should keep a tally. I'm told I'll be able to see detail in the rings, more than just the Cassini division. I've tried a couple times already to see it at the end of the night but it's usually so low that the atmosphere blurs it out.

However it's going to be a great Summer with Jupiter and Saturn, the Moon and the splendors of the Milky Way revealed in new detail.

I can't wait to show them all to you!

Bill the Sky Guy

Memorial Day, 2017

Jupiter is rising earlier every night and is now becoming well placed for viewing in the early evening through the new 10mm wide angle eyepiece I just got.

Well the new scope is here, put together and has been in service for a week. There were a couple bumps in the road but overall it all went pretty much as it should have. I made a video of the whole unboxing and assembly process so you can see how even though it's a big scope, it breaks down into easily (relatively) manageable pieces for transport to my stargazing venues. This was really important when you have to set it up and tear it down three times in a week! Here's the video:

2017 marks the beginning of a new era for Bill the Sky Guy. Because of the success of the Sky Guy programs at the Marriott Vacation Club properties here on Hilton Head it makes some sense to up my game a little (or a lot actually) with some new equipment so after doing a financial review of 2016 and coming to the conclusion that I needed to ‘spend it or lose it’, I have decided to purchase a new telescope.

While I really like the views through the scope I've had since 1986 and the mount is pretty accurate when it comes to finding things in the sky there are certain disadvantages when it comes to public viewing events. When you are looking in certain areas of the sky at certain heights (less than 45° up in the East or West) the nature of putting a Newtonian design scope on an equatorial mount means the eyepiece of the telescope ends up in some damn inconvenient places, like directly on top of the tube such that you'd have to be seven feet tall to look in there without a step-stool or ladder! Definitely not kid friendly either.

One of the issues with trying to show sky objects to the general public is that there are relatively few ‘showpiece’ objects in the sky. You've got the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Mars (some years), Venus (from time to time) and a few big star clusters, the Andromeda Galaxy, Orion Nebula and that's about it. Also, quite a few people who attend my stargazes have never looked through a telescope before so the skills that I've acquired in seeing detail in ‘faint fuzzy blobs’ aren't present meaning that things that are relatively easy for me to see are barely discernible or even invisible to the novice observer. So what would help in this department? More light of course! And not just a little more light; if I was going to spend real money, I wanted a huge jump in light-gathering not just an incremental improvement.

More light means a bigger diameter telescope, the bigger the better but at a certain point the limiting factor becomes portability since I do three stargazes a week at three different locations. The new scope had to be relatively easy to move and simple to set up and tear down. Now your typical refracting telescope, once they get to eight inches in diameter or more are measured in tons, and are usually on some kind of concrete pier mount so I obviously won't be buying one of those.

A Newtonian Reflecting design telescope can be made in large aperture, compact configurations but there is still the issue of how to mount it. At a public stargaze you also need to be able to find objects fast; people usually aren't into looking very intently and carefully at just a few objects for a long period of time; they want variety and the objects need to be easy to see so you need a mount that can be computer controlled and find objects in the sky automatically at the touch of a button.

As it turns out the ‘Truss Bar Dobsonian’ mount design is the answer. A truly large telescope like this can be automated, kept close to the ground so you don't need a ladder to get the eyepiece for most objects, and can be designed in such a way it can be disassembled into easily manageable parts for easy transport.

So I bought a sixteen inch in diameter telescope for 2017 (picture in the header of this article) which has 400% more light-gathering power than my current eight inch scope. It can be set up and computer aligned to the sky in ten minutes and will spectacularly improve the views people will see this year at my stargazes.

So what's the downside? For strictly visual observing there isn't any! However if you've read any of the About page on this site you'll know that I've always been interested in (and repeatedly come up short with) long exposure, deep sky astrophotography of galaxies, nebulae and star clusters. This big new beautiful telescope will be great for taking photos of planets and other bright objects where you don't need a long exposure. The problem is that the Dobsonian mount design is and up/down, left/right kind of affair which is fine for tracking objects through the sky but over the long term objects appear to rotate in the field because the mount is not aligned with the spin axis of the Earth which is the central premise behind the design of the Equatorial mount design.

So am I giving up on photography? Nope. My current mount is an equatorial, and I have the camera equipment, auto-guider and control software already so all I need is the right photographical scope on the mount I currently have and that should do it.

I recently became aware of a design of scope called a Ritchey-Chretien Astrograph. It's a scope design that's especially well suited for photography because the images are clear and undistorted all the way out to the edge of the field of view. So I bought an 8-inch one.

I can plop this on top of my existing equatorial mount and begin the process of trying to figure out the software, hardware and procedures necessary to take pictures of things that are forty million light years away.

This thing is much more compact than my current 8-inch Newtonian scope and should be much more stable and require less counterweight on the equatorial mount I've been using.

In addition, it's not only for photography, you can look through it like any normal telescope so for those busy summer months at the resorts I can now field an extra scope to keep the wait times at the eyepiece down.

2017 is going to be awesome; I can't wait to get started!

Bill the Sky Guy

January 1, 2017

So it's been a solid year of astronomy; and that's a good thing! It's one thing to be interested in the sky and take your telescope out to look at it when you feel you have time and then it's another to go out one, two, three times a week every week for 50 weeks straight! In January I was doing every Wednesday at SurfWatch Resort but in May I added The Barony on Monday nights and then Grande Ocean Resort in July on Tuesday nights.

The frequency that I am out under the stars these days gave me a renewed appreciation for the progression of the constellations through the sky, night to night, season to season through a complete yearlong cycle which I've never really done before, in our 365 day trip around the Sun .

It was a good year for planets with Jupiter high in the sky and easy to see from early March into late June. Trying to pick up on the great ‘red’ spot (which has been decidedly gray looking the past few years) is always a challenge and seeing the dance of the four main ‘Galilean’ moons from night to night gives me a good chance to talk about the prospects of life on Europa because of the amount of water there.

From Sky Safari 5 planetarium software

Wednesday March 23rd at SurfWatch we were treated to a serendipitous view of the shadows of both Ganymede and Io on the cloud tops of Jupiter at the same time, just as Van Morrison's Moonshadow started to play on my Spotify Astroplaylist!

There was plenty more planetary to look at as by May it was easy to spot Mars and Saturn. Saturn is always a show-stopper but as a big bonus we got a close approach to Mars (best view since 2005 due to its elliptical orbit) so for months on either side of May 30th, we got some really good views with surface features and polar ice cap clearly visible. Looking at it up to three times a week I got to witness the rotation of the planet from day to day. Mars' day is 24 hr 40 min so over a couple weeks you could really identify certain continent-sized features and see them rotate their position until you were treated to a new batch of surface features in a few weeks.

Saturn is a sure-fire winner with the rings easily visible and I have to say I am proud of the views my eight inch scope gave up near it's limit of magnification with a nice crisp view and Cassini's division in the rings easily discernible. The ten-inch SurfWatch scope with a high quality eyepiece really stole the show though with some amazing views and sometimes upwards of five or six Saturnian moons could be seen swarming the system.

Mars and Saturn were fairly close to each other in Scorpio during the peak viewing months but as we overtook Mars in our faster, inside orbit I was amazed at just how fast Mars' motion became against the background stars! It seemed like it would move 5° in the sky in just a week and very quickly overtook and passed Saturn in it's right to left (West to East) path in the sky on the Ecliptic, which is the plane of the planets in the solar system projected on our sky.

As the year waned I decided to put some of the big aperture we had available to good use and would track down the ‘you know it's out there but hardly anybody's seen it’ planet Uranus. They say that technically Uranus is within detectability of the naked eye (although no one noticed it until William Herschel discovered it telescopically in 1781) so I was expecting that once located it would be fairly obvious in a substantial telescope.

Strangely enough it was harder to locate than I thought. The computer GoTo system delivered me to the proper area of the sky (no real easy to find stellar ‘landmarks’ in this part of the sky for me) but all I saw were about 4 objects in the field and none of them looked particularly planetary. I took a good look, selected the bluest one and centered it and started pumping up the magnification. I had to get up well over 200x before this thing even remotely started exhibiting the disk-like look of a planet and even then it wasn't totally obvious until you compared it to the more point like look of the stars in the field. Needless to say we were all ‘underwhelmed’ but at least we could all say we saw it. I suppose I should give it a break, it's only four times larger than Earth but it's also nearly 2 billion miles away.

As we amateur astronomers are fond of noting we are specialists in tracking down and viewing ‘fuzzy blobs’ and with decent sized scopes there is quite a ‘blob assortment’ out there!

From Autumn through the early Winter the Andromeda Galaxy is a great target because it's huge, bright and even inexperienced observers can see the fuzzy nucleus of this nearest major galaxy to us. It's also fun to challenge people to find the companion galaxies M32 and NGC 205 and talk about the similarities to the Milky Way with our companion galaxies and how we (along with M33 in Triangulum) make up the Local Group galaxy cluster.

The Great Andromeda Galaxy with companion galaxies M32 on the left and NGC 205 lower right.

Andromeda is also (just barely) a naked-eye object and it's fun to use my laser pointer to show people how to find it using either Cassiopeia or the Great Square of Pegasus and tell them that it's the farthest away thing that you can see with your eyes and the light that hit their eye just now had been traveling for 2.3 million years which definitely gets one thinking.

Other Winter Fuzzy Hits Include the Great Orion Nebula which, late in the evening on some of the more transparent nights, has been positively breathtaking at 110x magnification. It's challenging and fun to look for the hard edges in the nebulosity and see how far you can trace them out away from the main center star cluster, the ‘Trapezium’.

M42, the Great Orion Nebula

I also enjoy showing people galaxies M81 and M82 in URSA Major off the bowl of the Big Dipper. Best from February through July these two galaxies have great contrast in character with one being edge on and the other face on but tilted and you can see them in the same field of view at low to medium magnification. At 40 million light years away they are twenty times farther away than Andromeda's M31 yet are still considered relatively nearby as galaxies go. That'll get ya thinking' about the size of the Universe!

M81 (lower left) and M82 (upper right) are as interesting as two galaxies in one view can get!

In the pre-computer guided days I used to shy away from showing people these two galaxies because they're semi-hard to find, kind of off by themselves in the North and not near anything all that bright. It used to be ‘guess, point and pray’ but with an audience, the GoTo function is a godsend!

M57, the Ring Nebula

As you get into Spring and Summer you get the Summer Triangle up high in the sky. Comprised of the bright stars Vega, Deneb and Altair this is is the amateur astronomer's giddy playground! There are all kinds of great objects in this part of the sky of many differing types. There are star clusters like the MegaHit M13 globular, planetary nebulae like the Ring and Dumbbell, delicate little open clusters nestled in the heart of the Milky Way like M71 and my all-time favorite object, the Veil Nebula complex. There's even a cluster that looks like a coat-hanger in the binoculars for the kids!

You can't do summer observing without getting to the area around the center of the Milky Way in the vicinity of Sagittarius and Scorpio. A really good object to show people has turned out to be M8, the Lagoon Nebula which ends up being a ‘three for the price of one’ object with a star cluster, reflection nebula, and dark nebula all in the same object. And of course there are a couple dozen interesting other star clusters and nebulae in the area that you almost can't avoid running across just sweeping your scope around. The gigantic star cluster M7 is always a hit in the Binoculars and i encourage people to commandeer the binoculars and see what they can stumble upon in this area of the sky.

Looking forward to doing it all again and better in 2017

Bill the Sky Guy

December 26, 2016

The Supermoon on Nov. 14th was supposed to be a good one. The close approach of the Moon in it's orbit was to be very close to the time of full Moon, more so than any Supermoon since 1948 I think I remember reading.

I have seen some Supermoons in the past and yes, they look big and bright, but so does every full Moon. It's a little hard to compare them since the last time I could have seen a full moon was 28 days ago and do I really know just exactly how big and bright that one was? So honestly I wasn't expecting anything all that stupendous but was happy that there was something about astronomy that was in mainstream media, perhaps since the Moon is an embarrassingly easy observational target!

The fourteenth fell on a Monday so I was going to be at my regular Monday stargaze at Marriott's ‘The Barony’ resort. Start time for those events is 8pm this time of year and I was expecting a good turnout since the weather was predicted to be clear that night.

One of the things about giving these stargazes right next to the ocean is that you get to see things rise over the ocean and nothing looks better than a full Moon rising over the ocean. Rise time this night was 5:56pm so I got there early and walked out to the beach with my camera and tripod since I knew there would be no way I could hold the camera steady enough for the length of exposures I'd be taking.

I got out early to select my spot and began to look around a bit. First order of business was to assess where the Moon was going to rise exactly over the ocean. For that I used one of those apps you can have on your smart phone that gives you a live map of the sky behind your phone as you hold it up to the sky. I could see where the Moon was just below the horizon and then referenced that point to a boat mast from a sailboat that was parked on the beach. So now that I knew where the Moon was going to rise (I wanted to see if I could get a good shot of the Moon only partially risen over the ocean) I turned my attention to the deepening twilight west with the brilliant planet Venus in the skyglow.

The hardest part about taking a photo of this scene is the tremendous difference in brightness between the sky and the land. If you just focus on the sky you get a bright dot against a sky, not an engaging shot so you want to get some land in there to get some perspective on the scene. Problem is the land is so dark compared to the sky if you expose it well the sky is so bright you lose the look of the sunset sky. Enter high dynamic range photography, also known as HDR.

Your eye can see more than ten, up to perhaps fourteen f-stops (brightness levels) whereas your average camera can do about 5-8, and a really expensive digital camera can do eight to eleven. My camera is nothing special but using HDR I can take pictures like this. The only real stipulation is you have to be shooting from a tripod and it helps if there isn't too much motion present in your shot (people running, bikes etc.)

What you do essentially is compose your shot, then take five exposures, one two stops too dark, then one stop too dark, correct exposure, one stop too bright and two stops too bright. I then run this photoset through a program called Bracketeer (there are many software tools to do this, I'm not saying Bracketeer is the best but it's inexpensive and does the trick) and it picks the best exposed parts of all five images and infuses them all together into one image that has the dynamic range of a really good camera or the eye.

Here is the shot I got:

An HDR photograph of Venus setting in the West

Moonrise over the ocean is always great (there's a couple shots of normal full Moons rising in Gallery page here) but this one had the potential to be spectacular! I got reacquainted with the rise point and as 5:56pm came and went I didn't see anything at first until about a minute into I saw a brilliant red arc, red as a stop sign, appear over the ocean beyond a ship!

I was amazed how red and bright it was and I scrambled to get the camera zoomed and focused and start taking pics none of which came out because they were blurred by the act of my finger pressing the shutter–these were 3-4 second exposures. I have since resolved to use the timer.

I was also amazed at how fast the Moon was rising, which made it very difficult to try and get many exposures hoping that one would come out both in focus and properly exposed.

My best result was this one:

Supermoonrise over Hilton Head Island, November 14th, 2016

It only takes the Moon two minutes to get up over the horizon so once that event was passed I shot about one hundred and fifty exposures in every possible camera setting and composition I could think of until a few minutes before 7pm when it became time to set up the telescopes. I grabbed the camera and tripod and made my way to the car to retrieve the scope and accessories.

I spent the next hour setting up my telescope and the one The Barony bought for the stargaze events. There are a lot of little details to attend to so I wasn't really monitoring the Moon's progress through the sky but wasn't lacking for light while I was setting up for sure! By the time I was set up the Moon had risen about a third of the way up and was looking amazingly bright. A good Supermoon is both larger and brighter than a regular full Moon; 14% larger and 30% brighter. The Moon looked large for sure but the thing that really blew me away was the brightness! I have never seen one this bright before. I put the 10-inch scope on it in preparation for the guests arrival and was getting it all focused and centered.

Any time you look at the Moon through a scope, when you are done you're eye will have stopped down due to the tremendous amount of light hitting it, giving you that ‘blind in one eye’ feeling as you step away from the eyepiece. Usually you're back to normal in thirty seconds but after this it took like a minute and a half! I was amazed and made sure to mention it to people as they were looking so no one would potentially lose their balance coming away from the eyepiece.

I had my scope showing a close as possible view that still kept the entire disk visible while got out my best 2-inch eyepiece and barlow lens for a 160x view at some of the more interesting areas like the heavily cratered region around crater Tycho (featured prominently in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey) and it's long ejecta rays that can be traced for hundreds of miles.

With a Moon this bright there was really nothing else to look at that night so we kept moving the high power view to new locations until everybody had had their fill. At the end of the night, the ‘die-hards’ and I tried to look at some other things but it was just useless, the Moon was just too bright.

Here are a couple more photos of the moon rising over the ocean.

Bill Gwynne, aka Bill the Sky Guy

The Supermoon about one half hour after moonrise.

Lucky dog; now there's a Moon to howl at!

One of the great(?) things about amateur astronomy is the fact that there is almost no end to the amount of accessorizing you can do! Forget shoes and jewelry, gimme focusers, auto-guiders and computer pointing control!

As the years go by, it seems like less and less of my scope hangs in there through each upgrade. The latest victim: the focuser.

There were two issues with my old focuser, one was that the speed it moved was too fast making it hard to achieve good focus without running right by it; it was stiff and the tiniest movement of the knob moved the eyepiece a LOT. The other issue is that there was this one rough spot in the travel that always seemed to be where you wanted to be.

So a quick visit to the online sites revealed that if I wanted to, I could spend over $500 on a new focuser! Well my rule is that I don’t spend more on a single accessory than the cost of the entire scope so I looked for something a little more reasonable finally settling on a Crayford design focuser from Orion for $80. It didn’t have the two knobs for two rates of travel but those were two and a half times the price.

In no time at all there was a box in front of my door (with a couple other things in it as well) and it was time to assess how to get it on to the scope. I didn’t have any illusions that the screw holes for the old focuser would match the new ones but what I wasn’t prepared for was that the size of the actual hole in the side of the tube was too small! So that left me with the dilemma of how to cut a circular hole on a tube where you can’t mark the center because there’s a hole there already. My solution: do something else! The tube is made of plastic so I thought that if I could draw a reasonable circle around the too small but perfectly cut circle that was there I could use a really rough file to widen the hole to its new width. Precision wasn’t terribly important since the base of the focuser itself would cover any little gaps between the focuser barrel and the tube. So one rat-tail file and 1/2 hour of elbow grease later I had something that worked.

A "Crayford" design focuser to replace the old rack and pinion one

I knew this was going to be messy business so I had to take my scope apart–ALL the way. I’ve never had it this far apart before but fortunately Newtonian reflectors are pretty easy to maintain and adjust with nothing more than a standard screwdriver and a couple of hex wrenches. So off came front assembly that supported the secondary mirror and the main mirror cell in the back (great opportunity for mirror cleaning) leaving me with nothing but the bare scope tube.

After a couple test fits I had the hole just wide enough to accommodate the focuser then it was time to get it on there straight, mark some hole drilling spots, drill and screw it on there.

Anxious to check it out I set up the scope behind my car in the parking lot of my condo. The only real target in the sky that night was a nearly full moon so that’s what I looked at. This new focuser is a lower profile model which is generally good for carrying the scope around and such but created an unknown in the area of what combination of extension tubes and 2” to 1.25” adaptors and such I would need to reach focus with all my nine various eyepieces.

The big task was to go through every eyepiece both with and without a magnification boosting barlow lens and see where they achieved focus best and whether there was a kind of “new standard setup” would emerge that would allow me to change eyepieces and refocus quickly at the stargaze events I run; nobody wants to stand around and watch me fiddle with the equipment for more than a few seconds.

New focuser looks great and is smoooooth!

During all this I saw a bunch of really great views of the moon, from 19x to 508x power. Honestly the extreme high power views were not that great and the eyepiece lens size you have to look through is so tiny that it’s almost useless if you wear glasses like I do.

There’s a guideline regarding scope magnification amounts that’s good to keep in mind: for every inch of scope width (diameter) you have, under perfect circumstances, you can only really achieve 50x magnification before your image turns to smeary mush. However, things are never that perfect, especially all at the same time. The term “perfect circumstances” refers to the combination of equipment quality plus seeing conditions so that means, perfect mirrors in your scope, $500 eyepieces and remote mountaintop observing conditions with a perfectly still atmosphere all the way to space. Obviously that never happens, especially all at once so the real magnification amount is usually about 25x per inch of aperture.

This is about right since my 8-inch scope’s image starts looking pretty ratty once you get up past 200x. The good thing is that you don’t need powers that high for most objects; only planets, close double stars and small planetary nebulae. I honestly do 85% of my viewing at 125x or less.

Also in the box was a finder “scope” known as a ‘reflex sight’. The reason I put the word scope in quotes is because these things don’t actually do any magnification but instead superimpose a red dot on the sky when you look through it. When I saw these things come on the market I initially questioned their value since they don’t magnify at all but they’re a part of the standard setup for the scopes we have at Marriott’s SurfWatch and The Barony and I have to say I find them quite useful during the alignment run at the beginning of the night.

Because of the nature of my scope/mount setup, when looking at certain areas of the sky the eyepiece can end up in some awkward viewing positions requiring getting up on the 2nd step of the stepstool or having to crouch down when looking near the horizon.

To make it easier for people to get to the eyepiece (since not everyone does Yoga) I bought a little thing called a “star diagonal” which gives the light a 90° bend for a better viewing angle. These are commonly sold with refractor and Schmidt/Cassegrain style telescopes as a necessary standard accessory.

Over the years I have taken off, put on, and taken off again a number of things which has left more than a couple holes in the tube. Every now and then some stray light will get in through these holes and ‘pollute’ a view I’m trying to get which is especially annoying if that something is a dim galaxy or whatever. So the last thing was to plug these holes and since I couldn’t find a variety of WD-40 that was dark enough, I went with duct tape!